This article is part of the series “Permanence might be all you need“. The series documents a side project of mine in which I explore invariant learning.

Also in this series:

- Priors and Invariants, a Primer

- Permanence – One Prior to Rule Them All?

- [coming soon] Learning Continuous Concept Spaces

- [coming soon] Instantiation and Feature Binding in Neural Networks

- [coming soon] Deeply Meaningful Representations with PtolemyNet

- [coming soon] Towards Predictive, Generalizing World Models

From invariant representations…

In machine learning, we often represent the state of a system as vectors. Artificial neural networks take the vector representation of an input, and transform it into a different vector which components are more meaningful to the problem at hand.

Such a vector representation is said to be invariant under operation X, if you can apply X to the model’s input without changing the resulting vector that comes out at the other end of the network. For example, an image classification network might turn a set of pixel values (input) into a vector where each component represents a particular type of content, e.g. whether the image contains a dog, a cat, a car and so on. This resulting representation of the image can be said to be invariant under operations such as:

- global brightness change – a dog is a dog, no matter whether the picture has been taken in bright daylight or at dawn

- translation – a dog is a dog, no matter whether it appears a little more to the left/top or to the right/bottom of the picture

- scaling – a dog is a dog, no matter whether it fills 10% or 50% of the image due to different distances from the camera

- change of background – a dog is a dog, no matter whether it’s depicted on a sidewalk or on a patch of grass

The above are typical invariants that are often desirable in computer vision tasks. In our everyday lives, we assume many other invariants, such as:

- object permanence – the car key is on the counter where I left it, even if I can’t currently see it because I’m in the other room

- a typical car’s function is invariant under differences in color – a red car will behave and drive about the same as a blue one

- a cup’s ability to hold liquid is invariant under changes of the specific liquid – it will hold water just as well as milk or wine

- … and numerous more

However, these invariants are rarely universal. Color invariance for example applies to a lot of everyday objects besides cars, but it doesn’t apply to traffic lights.

Illustration of selective color invariance: Imagine you’re an intelligent agent trying to safely cross the road. The middle and right images each differ from the left one in the color of one object in the scene. While the solution to your objective is invariant under color changes of the car (and for that matter, most other objects in the scene), the color of the traffic light is of significant importance. (based on a photo by Jacklee, Wikimedia Commons)

Can we still learn such “almost invariants”, and then fine-tune when they should be applied and when not?

…to invariant-separated representations

Rather than aiming for fully invariant representations, it appears helpful to aim for something a little different: a representation that separates out the aspects of a concept that are invariant under a given change, and the aspects that are not.

For example, imagine a representation for objects of different types. A color-invariant representation of an object would be identical, no matter whether the object is blue, red or green. As we have seen, such a representation is oftentimes useful when we deal with cars, but it is a very poor representation when used on traffic lights. Instead, let’s say that we have a representation that can be cleanly divided into two parts: the first part represents the type of the object and its various properties other than its color, and the second part represents only the object’s color.

I’ll call such a representation an invariant-separated representation.

This notion is analogous to what Yoshua Bengio et al. refer to “disentangl[ing] factors of variation” in Representation Learning: A Review and New Perspectives.

Two vector representations of objects. The left one mixes the type of the object (car, light, etc.) with the color of the object, while the right one is invariant-separated with respect to the object’s color. Note that neither representation is fully color invariant, as both still encode the color of the object.

Observe that invariant-separated representations have several interesting properties:

- No inherent information loss. While fully invariant representations inevitably discard some information, an invariant-separated representation can in principle maintain all available aspects of the concept they represent.

- An invariant-separated representation can trivially be transformed into a (fully) invariant one, simply by discarding the dimensions of the representation that code for the non-invariant aspects.

- Different tasks can utilize different components of an invariant-separated representation. Say that we have figured out how to obtain a location-separated representation of objects in an image. For classifying the types of objects in the image, we can ignore their locations. However, this representation just as easily allows us to learn location-based concepts such as one object “being on top of” another. Once the concept of “being on top of” is understood, the location-separated representation can apply this concept to any pair of objects by ignoring the dimensions other than location. In both cases, we gain strong generalization power.

In the previous article, we had talked about transformers as an example of a permutation-invariant model architecture. However, this is not entirely true: most practical applications of transformers, such as the GPT language models or the ViT vision models, add positional encodings to the input vectors to convey their positions within the input sequence. This is actually an example of an invariant-separated representation! The information about the position within the sequence is represented independently from the token or embedding itself. Just like in our color of car vs. color of traffic light example, the transformer can opt to ignore these positional encodings in one scenario, but pay attention to them in another.

Introducing the permanence loss

Neuroscientist Peter Földiák developed the concept of Trace learning (see Learning Invariances From Transformation Sequences). From the abstract of his paper:

“The visual system can reliably identify objects even when the retinal image is transformed considerably by commonly occurring changes in the environment. A local learning rule is proposed, which allows a network to learn to generalize across such transformations. During the learning phase, the network is exposed to temporal sequences of patterns undergoing the transformation. An application of the algorithm is presented in which the network learns invariance to shift in retinal position. Such a principle may be involved in the development of the characteristic shift invariance property of complex cells in the primary visual cortex, and also in the development of more complicated invariance properties of neurons in higher visual areas.”

Inspired by this observation, I propose the concept of a Permanence Prior to apply a similar idea to the machine learning domain. The idea behind the permanence prior is to encourage a model to learn a representation of its inputs that remains as “stable” as possible as we progress through time.

Assume an auto-encoder network A: ℝᵈ ⟶ ℝˡ that transforms an input vector I into a latent representation L = A(I). In and of itself, an auto-encoder would not be incentivized to learn any particular invariants, or to learn L as an invariant-separated representation of I. Its only goal is that L provides enough information to approximately reconstruct the input through a corresponding decoder network A⁻¹(L) ≈ I.1

However, just as with trace learning, we can utilize temporal sequences of inputs to learn properties of the input that remain (approximately) unchanged under local progression of time.

Assume that we don’t just have single inputs I, but now have a sequence of inputs Iₜ over time. We can calculate how the latent representations generated by A when applied to these inputs changes over time as a difference vector 𝛥 = A(Iₜ) – A(Iₜ₋ₒ) for some time offset o.

I define a permanence prior as a loss function P: ℝˡ ⟶ℝ that we apply to such a difference vector 𝛥, and which fulfils the following properties:

- Differentiable almost everywhere in ℝˡ

- Even in each component: P((𝛥₁, …, 𝛥ᵢ, …, 𝛥ₗ)) = P((𝛥₁, …, -𝛥ᵢ, …, 𝛥ₗ))

- Symmetric under permutations of the components: P((𝛥₁, …, 𝛥ₗ)) = P((𝛥ₚ₍₁₎, …, 𝛥ₚ₍ₗ₎))

- (Non-strictly) Monotonically increasing in the magnitude of each component: P((𝛥₁, …, 𝛥ᵢ, …, 𝛥ₗ)) ≤ P((𝛥₁, …, 𝛥’ᵢ, …, 𝛥ₗ)) whenever |𝛥ᵢ| < |𝛥’ᵢ|

- Among two vectors of equal magnitude, assigns lower values to the sparser one. More formally, take any two non-zero vectors 𝛥, 𝛥’ where 𝛥’ is equal to 𝛥 except with one of its non-zero components set to zero, i.e. 𝛥’ = (𝛥₁, …, 0, …, 𝛥ₗ). Then we require P(𝛼/||𝛥|| * 𝛥) > P(𝛼/||𝛥’|| * 𝛥’) for any magnitude 𝛼.

Choosing a permanence loss function

There are several functions that fulfil the properties of a permanence prior laid out above. A simple choice is the usual L1 norm. However, notably, the L2 norm is not a candidate, as it does not fulfil property 5.

A downside of the L1 norm for our purpose however is that its value grows proportional with scaling of the difference vector (||𝛼𝛥||₁ = 𝛼||𝛥||₁). Thus, it significantly penalizes delta vectors of larger magnitude. Our goal though is not an overall time-invariant representation, but an invariant-separated representation. We merely want to ensure that the difference vector is sparse, not that it is necessarily small.

The following function achieves this goal better:

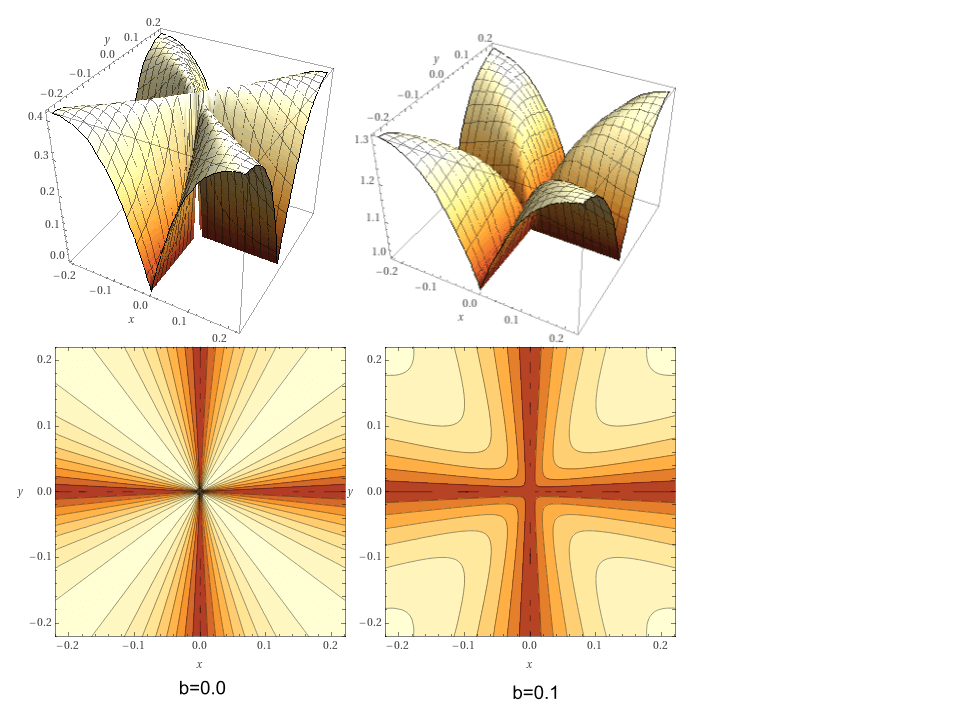

Pb(𝛥) = (||𝛥||₁ + b) / (||𝛥||₂ + b)

where b∈ ℝ⁺ is a bias value, and ||∘||₁ and ||∘||₂ are the L1 and L2 vector norms respectively. A value of b=0 makes the function entirely scale-invariant. A larger value of b allows more “wiggle room” for non-sparse difference vectors as long as the magnitudes of the non-sparse dimensions remain small. In my experiments, a small but positive b has resulted in better convergence of the model under gradient descent.

P₀ and P₀.₁ in two dimensions

Intuitively, these functions measure how “sparse” the change of our encoder’s latent representation is across time. It thereby incentivizes latent representations that, under local progression of time, change only in a limited number of dimensions, while remaining stable in as many others as possible. The aspects of the input that change over time will be encouraged to get separated from the aspects that remain unchanged.

We can now train an auto-encoder by complementing the usual auto-encoder loss (e.g. ||A⁻¹(A(Iₜ)) – Iₜ||) with the permanence loss P(A(Iₜ) – A(Iₜ₋ₒ)) to work as a regularizer. The auto-encoder loss function makes sure that salient features of the input are maintained in the encoding, while the permanence prior nudges the encoder to produce latent encodings that change sparsely over time.

Permanence loss encourages invariant-separated representations

It turns out that for certain sequences of real-world sensory data, the permanence loss prior is sufficient for deriving invariant-separated representations for several useful invariants.

Imagine an artifical life form (or robot for that matter) moving around in our three dimensional world. The life form has an eye to observe the world. It can move its eye to change its direction of view, tilt its head, walk around and so on. For the sake of the argument, we assume that the life form’s neural networks are trying to learn an auto-encoder style representation of its world, i.e. one that permits approximately reconstructing its inputs from the representation.

As the life form shifts its gaze, the image appearing in front of its eye shifts as well. The permanence prior will favor a representation of the visual image that separates information about the life form’s current direction of gaze, from the contents of the image. It will learn a representation that is invariant-separated under a shift in perspective.

As the life form tilts its head, the image will rotate. A representation that minimizes the permanence loss, while maintaining a low reconstruction loss, will be one that is invariant-separated under rotation.

As a cloud moves in front of the sun, the life form observes the image become darker from one moment to the next. A representation with minimal permanence loss will be one that is invariant-separated under brightness change.

Next up, assume the life form observes other animate objects. It might look at the leaves of a tree moving in the wind, a pebble rolling down a hill, or a fly buzzing around. A representation with low permanence loss will be one that understands the boundaries of an object in the image, with the object’s location explicitly expressed, as this allows the animate object to move around with only a minimal change in the representation vector. Therefore, permanence loss appears suitable for learning a notion of “objectness”, or more precisely, separating a scene into components that can move independently of each other.

These are already quite meaningful invariants that all arise from observing a sequence of visual stimuli over time. If we now allow the life form to also have a form of memory, and apply the permanence loss not only at short time frames (e.g. from one second to the next), but also over longer time frames (minutes, hours or even days), we can plausibly expect that properties such as object permanence to arise. Even an understanding of certain physical preservation laws can arise as being explicitly encoded in the life form’s representations. For example, the realization that the number of pebbles in a jar does not change when I shake the jar would lead to a representation where the count of objects is invariant-separated from count-preserving properties such as the particular arrangement those objects are in.

The limits of invariant learning through permanence loss

As we have seen, a permanence loss prior can encourage a neural network to learn representations that directly represent powerful invariants.

However, it is important to note that the set of invariants that can be derived through learning with a permanence prior are heavily dependent on the temporal patterns that are present in the training data.

In fact there is a class of similarly meaningful invariants that will not arise naturally from permanence. We motivated our exploration of invariant-separated representations by looking at how the color of an object is represented. As it turns out, color separation is probably not a good property to be separated through a permanence prior. In our everyday experience, the color of an object changes rarely. Traffic lights and other human-made contraptions are probably the biggest exception. Hence, permanence loss would not act strongly on the encoding of color, and might leave it “entangled” with other rarely changing properties of an object.

The way I think about it, there are two types of invariants in our world, though this might not be an exhaustive categorization:

- Temporal invariants, which describes properties that can change over a period of time without impacting other aspects of the world, and

- Instantiation invariants, which can differ from one instance of a concept to another without impacting other aspects of the given instance (but might not change for the given instance over time)

In our world, the location of an object is an example that matches both categories. For one given object, its location can change over time as the object moves around, without changing other properties of said object (temporal invariant). Location will also differ between multiple instances of an object class however, usually without otherwise impacting the nature of those objects (instantiation invariant). Many temporal invariants are also instantiation invariants, but the inverse is not always the case.

Traffic lights aside, the color of an object is largely an instantiation invariant. Cars for example come in various different colors, and their colors have little bearing on their function and behaviors (instantiation invariant). However, the color of any one given car doesn’t normally change over time.

Permanence loss helps learn temporal invariants. Instantiation invariants have to be learned through other means. However, there is an argument to be made that permanence loss can help a neural network more effectively learn instantiation invariants as well. Remember that we outlined above how permanence loss could help a neural network learn the concept of “objectness”, the fact that different objects in our world can move and act independently of each other. Once the notion of an object has been established in a representation, and therefore also the notion of an single instantiation of the object’s class, subsequent layers of neural nets might have an easier time deducing instantiation invariants as well!

All this of course is quite speculative, but I believe there are some intriguing potential properties here to explore and validate.

What’s next?

In this post, I introduced the concept of an invariant-separated representation, and then proposed a permanence loss prior that encourages neural networks to learn such representations based on temporal data patterns.

What we’re missing is a neural architecture that is efficient at learning permanence-driven invariant-separated representations at different levels of abstraction. Simply adding the permanence prior to a regular fully-connected deep neural network is unlikely to cut it. For example, consider the task of separating an object’s position from its class, color or size, given a sequence of bitmap representations of video frames. While separating the x and y position of an object is learnable by such a network, this task would likely be extremely sample inefficient. In particular, interpolation in the positional domain would not happen effectively, as there is no inherent notion to connect each individual input pixel to its relative location within the image.

In my upcoming post, I’m going to discuss how we can learn concept spaces – continuous metric spaces that allow us to embed discrete properties of the world into an interpolatable manifold. Besides permanence loss, the ability to learn and efficiently operate on such spaces is going to form the second important insight towards sample-efficient representation learning in the PtolemyNet architecture.

Footnotes

- Auto-encoders trained with their reconstruction loss are only one way of learning meaningful representations. A promising alternative to auto-encoders is the Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture, or JEPA for short. Either could be combined with the permanence prior. ↩︎

Leave a comment