This article is part of the series “Permanence Might Be All You Need“. The series documents a side project of mine in which I explore invariant learning.

Also in this series:

- Priors and Invariants, a Primer

- Permanence – One Prior to Rule Them All?

- [coming soon] Learning Continuous Concept Spaces

- [coming soon] Instantiation and Feature Binding in Neural Networks

- [coming soon] Deeply Meaningful Representations with PtolemyNet

- [coming soon] Towards Predictive, Generalizing World Models

We need priors to learn

If you’re already familiar with inductive priors and the No Free Lunch Theorem, feel free to skip this section.

Intelligence is the ability to utilize past experience in order to respond intelligently to new, previously unseen situations. Responding intelligently typically means responding in a way that increases the likelihood of achieving a desirable outcome, such as correctly stating whether a given picture contains a cat, finding the exit of a maze, or staying alive and procreating.

Unfortunately, the No Fee Lunch Theorem (D. Wolpert 1996) tells us that it is impossible to intelligently generalize from previous experience – if that experience is all we know about the world. Without knowing anything else about the world, a computer vision model that aims to determine whether a given picture contains a cat can at best remember all the pictures it has been shown during training, and give a confident answer about the cat-ness of the picture when shown the exact same picture again. However, there is no universally true way to derive a statement about any other, not previously seen picture.

In order to generalize beyond a model’s training data, priors must be introduced. Priors, short for “a priori” knowledge, are properties of the world that are assumed to be true. For example, we might assume that if we start with a picture containing a dog, and then see another picture that differs from the first one only in small changes to each pixel’s brightness value, that the second picture still contains a dog. This particular assumptions, that small changes in the numeric values of the inputs will typically not cause dramatic changes in the meaning of that input, appears to be a useful prior for many practical problems. ANNs trained with the common L2 or L1 regularizer will behave essentially like this – small changes in such a network’s inputs will rarely cause large changes in its outputs, since their internal weights will be encouraged to remain small.

However, such a simple prior is rarely sufficient.

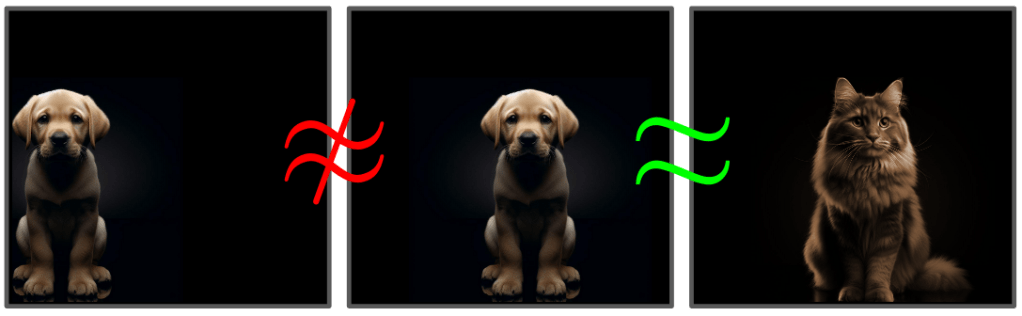

These images illustrate a failure case of simple L2 regularization: If one was to compare the pixel-by-pixel color values of the left and the middle images, one would find that there are major differences. Many pixels that are black in the left image are brown in the middle one, and vice versa. In comparison, the middle and the right image have very similar pixel values in the same places, with only small differences around the animal’s details. However, the left and middle image contain the same object class, a dog, while the right one shows an instance of a cat, an entirely different species of animal. A prior based on the similarity of input values would incorrectly steer the network towards classifying the middle and right images as being of the same class, while treating the first two as different.

Symmetries and invariants enable generalization

A very powerful class of priors are symmetries. Symmetries lay at the foundation of modern physics, and many of the physical laws of our universe can be derived from certain underlying symmetry properties (see Noether’s theorem).

For our purposes, a symmetry is defined by an operation that changes the state of a system, but keeps other properties of the system unchanged. The unchanging set of properties is said to be invariant under the symmetry operation.

An example of such a symmetry in maths is addition over natural numbers. The result of an addition is invariant under reordering of the operands. 1 + 3 evaluates to the same value as 3 + 1. (A mathematician would say that addition over natural numbers forms an Abelian group.)

In our universe, we assume that the same laws of physics apply in any location. When the Large Hadron Collider detected the Higgs boson at CERN near Geneva, we didn’t question if the same Higgs field would also exist in San Francisco. There is no such thing as Earth quantum mechanics and Mars quantum mechanics. There’s just quantum mechanics. We also assume that the same laws of physics that apply today are still going to apply tomorrow. In other words, we assume the laws of physics to be invariant under shifts in space and time. While we have no definitive way to prove that these invariants actually hold, we do assume that much when interpreting the results of a new physics experiment. They form a prior that enables us to generalize from discoveries in one location and time, to an improved understanding of physics at all locations and times.

Symmetry and invariance assumptions like these are what allows us to build models of the universe and of our environment. They’re the essence of what allows us to generalize from past observations to future situations.

I find it miraculous that our universe appears to obey such strong symmetries. However, it appears that life, and even more so intelligent life, could not exist at all in a universe that lacks some basic degrees of symmetry. Evolution only works if a cell can assume that the chemistry and cellular mechanics around its DNA are going to follow the same process tomorrow as they do today. Further, evolution requires that the environment of a life form does not change drastically from one generation to the next – at least most of the time. It seems safe to say that nothing of interest could evolve in a random, unpredictable environment with no symmetries whatsoever.

Symmetry assumptions lie at the heart of recent ML and AI breakthroughs

Basic computer vision tasks, such as classifying the type of object in an image, used to pose grave challenges to ML and computer vision engineers not all that long ago. It was only in 2012, when a deep artifical neural network called AlexNet (Krizhevsky et al. 2012) really jump-started the deep learning revolution by demonstrating near-human performance in this task. AlexNet benefitted from three important enablers:

- availability of GPUs that could be used for large-scale model training

- availability of large, crowd-sourced training data sets (ImageNet)

- last but not least, an ANN architecture called convolutional neural network (CNN)

Convolutional neural networks (CNN) go back to to late 1980s (Zhang 1988, Denker et al. 1989, LeCun et al. 1989), but were initially limited due to a lack in computing power and data availability. But in the mid 2010s, CNNs began to dominate computer vision. Only recently have we seen another architecture, vision transformers, starting to compete in this domain.

In contrast to a traditional “fully connected” artificial neural network, a convolutional neural network encodes only a single additional assumption: that the processing of an image is invariant under shifts in location within the image (translation invariance)1. Thanks to this symmetry assumption, you could train a CNN to distinguish, say, dogs from cats using only images of dogs and cats sitting in the lower left corner of the image. The resulting CNN would still be able to tell a dog from a cat if they appeared in the top right, even if it had never before seen an image with an animal in that part of the image. Traditional neural network architectures without such a prior would fail to generalize in this scenario.

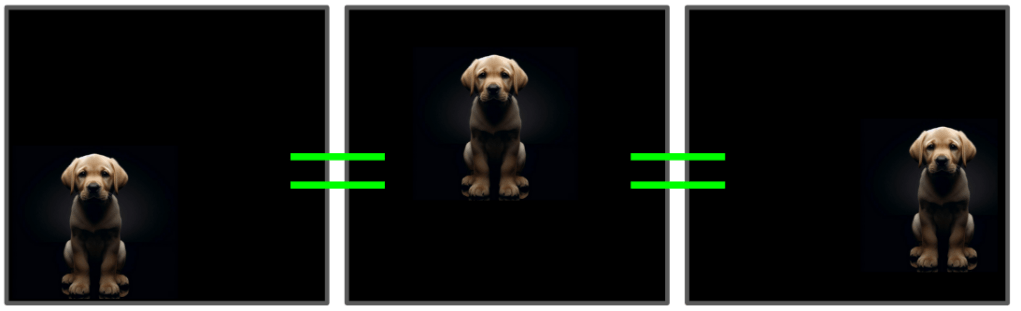

To a CNN, these three pictures look the same. Once you teach it what a dog in the left bottom of an image looks like, it will be able to recognize a dog anywhere else in the image.

Note that despite their success in understanding images, the symmetry assumption that is baked into the CNN architecture is nowhere comprehensive enough to capture all of the desirable symmetries that exist in image understanding. For example, rotation and scale invariance still have to be learned “the hard way”, by providing a sufficient number of samples at varying rotations and scales in the training data. (This is frequently accomplished through data augmentation).

Recently, a new model architecture called the transformer (Vaswani et al. 2017) has unlocked new advancements first in natural language processing, and more recently in computer vision as well (the Vision Transfomer, Dosovitskiy et al. 2020). At the heart of the transformer lies a different symmetry assumptions: permutation invariance. Permutation invariance ensures that the order in which input “tokens” are seen is irrelevant for their meaning. Translation invariance in images is related to permutation invariance, but acts at a different level of abstraction.

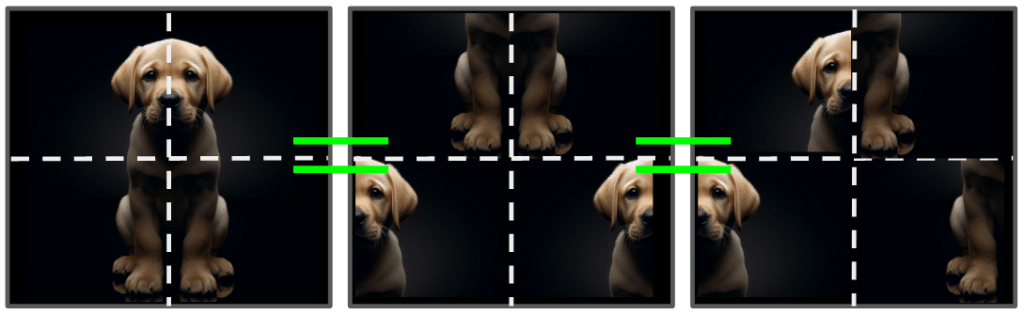

Illustration of permutation invariance. Assuming that the image of the dog is divided up into four patches/tokens, any permutation (reordering) of those tokens will be indistinguishable from each other to a transformer.

As it turns out, permutation invariance is actually a little too strong of an invariance for most practical applications. Most transformer-based models (including GPTs and ViT) therefore “add back” a way for the transformers to restore location and permutation awareness by adding a “positional encodings” to their input tokens. The ingenious thing about positional encodings in transformers is that the transformer can still maintain the benefits of permutation invariance at large, but can “choose” to attend to positional information only when it’s helpful. We’ll dig deeper into this concept of selective invariants in the next part of this series.

Learned priors: priors + data = more priors

Humans are frequently able to perform single-shot learning of new object classes or concepts. If someone shows me a single photograph of an animal species that I’ve never seen before, I’ll be able to recognize this same species in a different picture. Despite the incorporation of basic symmetries, most current machine learning approaches on the other hand require hundreds of samples of a new object class before they can reliably identify it in future data. In machine learning terms, one could say that humans, after having gone through a few years of pre-training on our world, become highly sample efficient, while many current ML approaches are sample inefficient.

We humans utilize a wealth of prior experience in this process. The set of priors we apply to understand a new, previously unseen situation are highly complex. They range from learned knowledge about how objects look as we move around in 3D space, over assumptions about how other people around us feel and behave, to knowledge about abstract concepts such as logic and mathematical relations that we utilize to quickly contextualize new information.

Where do we get these priors from?

For humans and other intelligent animals, some priors are surely encoded in our DNA and imprinted into us through the way our brains and brain chemistry are set up. But I suspect that the majority of our priors are learned through experience.2

Can we learn all the priors about our world from scratch, just by observing the world and interacting with it?

Surely not. This would be in contradiction to the No Free Lunch Theorem. However, what if we can find a small number of fundamental priors, such that all the more complex symmetries and priors can follow from them once we’ve been exposed to a sufficient amount of data? In other words, what could be a good starting point, such that, once combined with observed data, it allows us to “bootstrap” more and more successive layer of ever more complex priors? Each additional layer of learned priors would make us able to extract more and more useful information out future observed data, speeding up the training process and building a strong framework for generalization along the way.

What’s next

In this article, we’ve looked at the concept of priors, and why they are critical in extracting useful, generalizable information from observation. We’ve also introduced symmetries as a particularly strong type of prior. A type of prior so strong that our entire understanding of physics and of our universe is built on them.

Lastly, we’ve introduced the idea of learned priors. The idea that once we find the right priors to start out with, we might be able to grow an increasingly deep understanding of reality by inferring additional priors from the data as we go. We would avoid the need to hand-code all the complex assumptions and heuristics that give us humans our unmatched ability to learn and generalize new concepts from the smallest number of samples.

In the next part of this series, we’ll introduce the permanence prior as a possible candidate for bootstrapping this learning process.

Footnotes

- Strictly speaking, CNNs are translation equivariant, and not translation invariant. Though pooling layers in common CNN architectures can be thought of as turning the translation equivariant convolutions into translation invariant activations. ↩︎

- The distinction between a-priori (prior) and a-posteriori knowledge becomes a little blurred once we start talking about “learned priors”. However in practice, I think that the concept of a learned prior is still useful, in the sense that we can utilize structure we observed in past data points in order to increase the amount of information we can extract from a new future data point. The posterior of past data therefore becomes a prior for future data. ↩︎

Leave a comment